Sweet Thunder Background Notes

Novelists of course love trouble, as old and new a story as there is, so when I began thinking of another chapter of life for Morrie Morgan, itinerant teacher and "walking encyclopedia" who lit up the pages of The Whistling Season, Montana's onetime copper metropolis of Butte naturally came to mind.

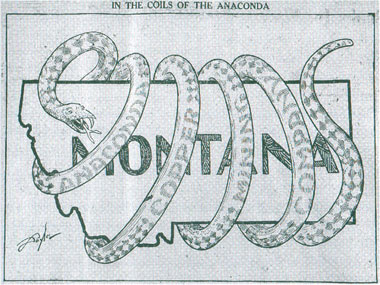

I'm from the other Montana, the one of wide open spaces and communities too small to be called towns, let alone cities--and Butte was known to us, when I was growing up out there in ranch country, as a place as crazily off the charts as, say, Las Vegas is today. Rough, tough, known for altitude and attitude, full of foreign accents and cosmopolitan vices, the mile-high city was dominated by the Anaconda Copper Mining Company--which also wielded behind-the-scenes power in state politics and owned all of Montana's daily papers but one, helping to send ambitious young wordsmiths like A.B. Guthrie and Norman Maclean and yours truly out of state so we didn't have to "wear the copper collar" as we pursued careers in journalism and literature.

|

|---|

Typical editorial page cartoon in the newspaper war during the Anaconda Copper Mining Company's political domination of Montana, circa 1920 |

It is there at the typewriter keys that I feel closest to Morrie, although my career as an editorial-page wordslinger was "back East' in Decatur, Illinois. I was fresh from Montana bunkhouses and the U.S. Air Force, and the job as an editorial writer was my first in journalism. I gave it all I had, blazing away at the typewriter in that grandest of inkslinger's goals, to write faster than anyone who was better and better than anyone who was faster. Not even the big stories that tended to break on my Saturday night stints as wire editor--the Valdez earthquake in Alaska, and the death of Pope John XXIII, yards of copy unendingly unfolding out of a row of teletype machines, did me in, quite.

As it turned out, my newspapering career did not go on--a magazine job and a woman named Carol lured me to Chicago, and a lasting change in my writing life—but I never lost touch with newspapers themselves, those blessed black-and-white-and-read-all-over repositories of history, and sometimes even literature, on the run. In my time as a freelance writer my byline appeared in the New York Times, Chicago Tribune, Denver Post, and Los Angeles Times, as well as the Seattle dailies here where Carol and I settled in our journalism-related careers. Perhaps it is small wonder, then, that Morrie, like me, falls in love with the newspaper life and the editorial writer's role of afflicting the comfortable and comforting the afflicted.

|

|---|

A Butte mansion, typical of "Horse Thief Row," during the city's copper boom. |